DOUBLE-ENTRY

The Bane of Modern Money Theory--Or its Generator?

In her book Double-Entry, Jane Gleeson-White casts a revealing light on the fundamental dilemma of Modern Money Theory. Interestingly, reading between the lines, her narrative also suggests a specific strategy for overcoming that very dilemma.

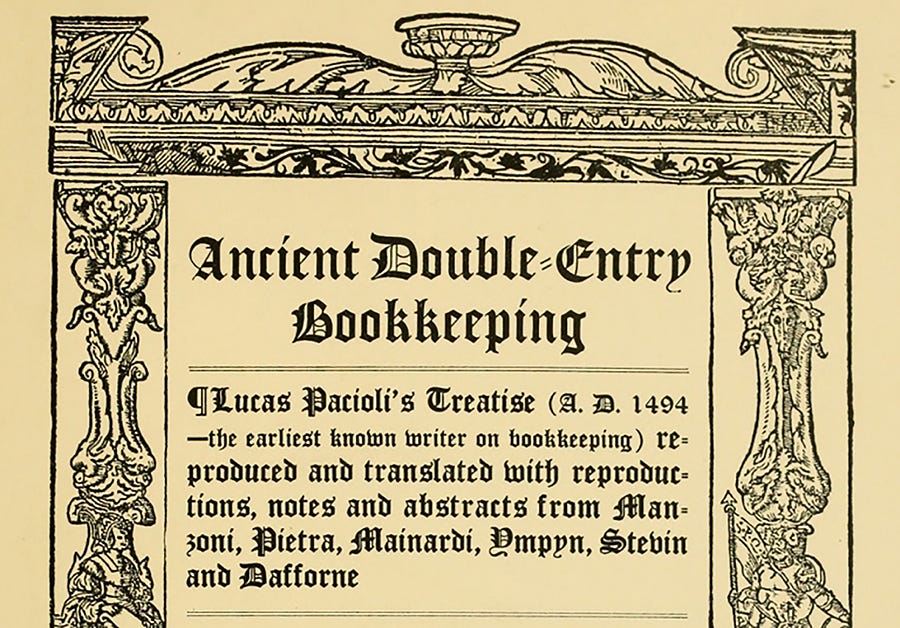

The book traces the roots of double-entry bookkeeping from the merchants of Venice and its first codified explanation in 1494 by a mathematician monk (and close friend of Leonardo DaVinci), Luca Pacioli. Pacioli’s explanation happened to be written just after the moveable-type printing press was invented and, as a result, was rapidly disseminated throughout Europe. Gleeson-White’s narrative traces the evolution of double-entry through the Renaissance, to the Industrial Revolution, through the invention of joint stock companies (i.e. corporations) and, eventually, the development of National Accounts which today calculate the Gross National Product and economic “health” of nations. Many things jumped out at me in the reading, but two gave rise to the topic of this essay:

First, double-entry bookkeeping invented the concept of financial “profit” which, of course, is central to the mechanics of modern banking and the Federal Reserve’s issuing of sovereign fiat money. The FED issues new Reserves—fiat dollars—in response to the profit-making growth of bank-loans, exchanging the new Reserves for assets from the banks which the FED then puts on the other side of its balance sheet. Double Entry: liabilities (new Reserves) = new assets.

Second, the process of double-entry bookkeeping (and the concept of financial profit) established our “normative” thinking about money—that is to say, the mental architecture with which we perceive and understand monetary operations. And it is this mental architecture, structured over centuries by the operations of double-entry bookkeeping, that makes federal “DEFICIT SPENDING” such a steep obstacle for Modern Money Theory to overcome: No matter how creatively MMT tries to re-frame it, “deficit spending” will always be defined by double-entry bookkeeping as “spending MORE than you earn.” Period.

Thus, it is virtually impossible for normative “money-think” to accept the MMT logic that taxes do not pay for government spending—and, therefore, government spending greater than tax revenues (deficit spending) does NOT create a national debt that must repaid with future taxes. The “impossibility” of accepting these as true statements is the fundamental dilemma of Modern Money Theory—a dilemma that makes it POLITICALLY IMPOSSIBLE to implement the government spending initiatives, benefiting the collective well-being, that MMT advocates. In other words, politicians floating the idea that things can be paid for with the mechanisms of modern fiat money simply cannot be taken seriously. And, knowing this, no serious politician is willing to advocate for the kind of government spending MMT demonstrates to be possible.

But here Double-Entry itself suggests a strategy to overcome this “Catch-22”.

The Federal Reserve Balance Sheet

As things stand in our “Standard Money Theory,” Congress directs the Treasury to spend dollars for this or that initiative and, in response, the Treasury issues Treasury bonds to raise the necessary funds to meet the spending directive. Ostensibly, the Treasury then collects taxes to pay the principal and interest on the bonds. Double-entry bookkeeping can only record this in one way: The Treasury’s assets are its tax revenues, and the bonds are its liabilities. If the liabilities (bonds) are greater than the Treasury’s assets (tax revenues) the balance sheet is in “deficit”—and, at some point tax revenues will have to be increased to bring it into balance. There is no logical way around this dire, bookkeeping calculation.

If, on the other hand, we look at the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve we see (surprisingly) that instead of recording “deficits,” Double-Entry records the CREATION of money. While this may at first seem oddly against the rules, if you consider that the Federal Reserve is the sovereign government’s agent for issuing fiat money, it seems perfectly correct: The Federal Reserve, under a standing government directive, issues fiat money—as necessary—to monetize the profit-making initiatives Private Enterprise decides, in aggregate, to undertake. Specifically, we see the FED issuing new fiat dollar Reserves (liabilities) in exchange for collateral (assets) to ensure that the end-of-day “clearing” process is always completed—i.e. every bank-dollar claim on the Reserves of another bank is met. The FED’s liabilities equal its assets—except the liabilities, in this case, are new fiat dollars it has issued into the Reserve banking system. Here, Double Entry puts on a new face—and we must ask the question:

If the FED can issue new fiat dollars to monetize private profit-making, why can’t the same mechanism be used by the Treasury to monetize not-profit-making initiatives benefiting the collective well-being? In other words, how can the Treasury pay for spending initiatives directed by Congress without issuing Treasury bonds—and without incurring the political wrath and confusion of “deficit spending”?

The answer is simple: Public Banks.

If non-profit Public Banks are chartered as part of the Federal Reserve banking system (as proposed by the federal Public Banking Act of 2023) the exact same Double Entry bookkeeping that issues new fiat money for profit-making enterprise can be applied to non-profit-making initiatives directed by Congress! The only difference will be the collateral the FED puts on its balance sheet in exchange for the new Reserves.

To see this, let’s take a specific example: Universal Preschool Childcare. You may recall Barack Obama proposed such a program in 2013—only to quietly withdraw the proposal a few months later because Congress couldn’t agree how to raise the NEW TAX REVENUES necessary to pay the $13 billion/year price tag. But let’s imagine the federal Public Banking Act has been signed into law—and every state in the union has a Public Bank that is part of the Federal Reserve system: How could Obama’s proposal be paid for now? Here are the steps:

As authorized by Congress, the Treasury directs the FED to establish a “deferred asset account” on its balance sheet specifically for the Universal Preschool Childcare program. (“Deferred assets” are current expenses for something which cannot be consumed in the current accounting period—and which will not be consumed until some point in the future. Bookkeeping-wise, they are not, therefore, entered as “expenses,” but as “assets”—something assigned a specific monetary value which can be consumed in the future.)

The Treasury then issues a directive to the federal Public Banks establishing the criteria for issuing loans to local and regional preschool childcare providers to pay for facilities, staffing, training, equipment, insurance, management, etc. These criteria would include a dollar-value expense for each “childcare unit”—say, $18,000 to provide preschool care and education for one child for one year. (The loans would be, in essence, one-time and recurring zero-interest grants.)

Existing and start-up local/regional childcare providers would then apply for loan-grants with their federal Public Bank. The Public Bank would evaluate the loan applications using the criterion established by the Treasury. Approved loans would result in bank-dollars being credited to the childcare provider’s bank account commensurate with the “childcare units” to be provided.

Simultaneously, the Public Bank would submit the “paid for” childcare units to the FED as “deferred asset collateral” in exchange for new Reserves equal to the approved loan. The FED would put the childcare units in the Universal Childcare deferred asset account on its balance sheet—and credit the new Reserves to the Public Bank’s Reserve account.

The childcare provider would write checks on their account at the Public Bank, the checks would go through the end-of-day clearing process at the FED and the bank-dollars in the checks would make their claims on the Public Bank’s Reserves—exactly the same process that “monetizes” the profit-making transactions of private enterprise.

To qualify for this “deferred asset spending,” the Congressional Budget Office must determine that a proposed initiative will provide a projected “monetized social benefit” greater than the projected expenses for the program—say, a minimum of two-times greater. For example, Nobel economist James Heckman has calculated the monetized social benefit for preschool care and education—measured in terms of enhanced social and emotional skills, better health outcomes, reduced social and law-enforcement costs, increased parental employment and earnings, greater family financial stability and spending power, etc.—to be $13 for every $1 spent. The “deferred assets” of universal preschool childcare, therefore, would qualify with flying colors!

Thus, Obama’s Universal Preschool Childcare program is financed across the country WITHOUT the Treasury engaging in “deficit spending,” without getting ensnared in political bickering about new taxes, and without the excruciating ordeal of having to increase the “national debt limit.” Even better, decisions about which businesses and organizations receive the childcare financing grants are not political decisions, and are not implemented by a politically controlled bureaucracy—they are banking decisions made with the due diligence of local and regional Public Banks who are specifically serving the needs of local and regional communities.

Double-Entry, then, brings Private Enterprise and Public Enterprise together under one umbrella: the normative, everyday operations of modern fiat money administered by the Federal Reserve banking system. If one can imagine it’s possible, the paralyzing political charade of federal spending by the mechanism of Treasury bond “borrowing”—and the consequent need for new tax revenues—is forever dispelled.

Now, perhaps, we can actually start doing something.

Maybe we can talk tonight about how the fact that 1$ invested produces 13$ of social value factors into this?